- Biweekly Engineering

- Posts

- Scaling Low-Latency System at Atlassian with AWS | Biweekly Engineering - Episode 44

Scaling Low-Latency System at Atlassian with AWS | Biweekly Engineering - Episode 44

How Atlassian built a latency-sensitive context service and ensured 6-9s of availability!

Welcome to the 42nd episode of Biweekly Engineering! Today, we’re diving into an interesting scaling saga from the team at Atlassian.

The Red Line protest in Hague, Netherlands against Gaza genocide (photo collected from Dutch news)

In this episode, we touch Atlassian’s journey to a low-latency system in AWS. The first article shares how the team built and brought the latency down for the specific system. The second article builds on top of the system and showcases how to ensure 6-9s of availability.

Without further ado, let’s start!

Atlassian’s Latency Sensitive System in AWS

The Challenge: The Tenant Context Service (TCS)

As Atlassian migrated to AWS, they needed a central source of truth to map customers (tenants) to their specific data locations (shards and databases). The type of data and shards are less relevant for the core message of the article. You can imagine that there is a need for gathering some data for each client/tenant. And there is a service built for that purpose.

So they built the Tenant Context Service (TCS).

The requirements were sort of strict:

Massive Scale: Tens of thousands of requests per second.

Ultra-Low Latency: It’s called multiple times per user request. Latency has to be sub-miliseconds.

High Availability: 99.99% to 99.999% uptime. If TCS is down, all of Atlassian Cloud is essentially down.

Here is how they evolved the architecture and the hard-won lessons they gathered along the way.

The Architecture: CQRS + DynamoDB

Atlassian opted for a CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation) pattern.

Catalogue Service: Handles the "write" side (updates) with strong consistency.

TCS: The "read" side, globally distributed across AWS regions.

Kinesis: Used to stream updates from the Catalogue to regional TCS instances.

While DynamoDB is a powerhouse, the team quickly learned that at extreme scales, the cloud is not a magic.

Lessons Learned

Lesson 1: Databases aren't fast enough

Even with DynamoDB's single-digit millisecond response times, network overhead and occasional spikes made it impossible to meet aggressive p99 goals.

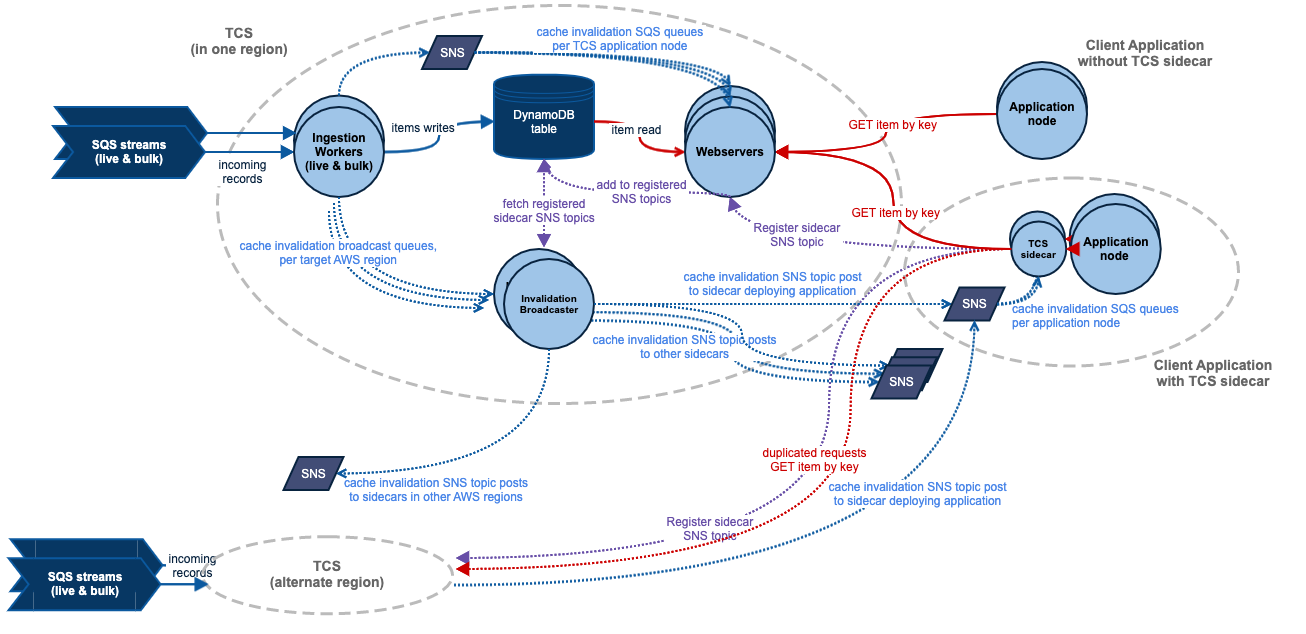

Fix: They implemented node-local caching. To keep caches updated, they used Amazon SNS to broadcast invalidation messages to every node. By avoiding the network for most reads, latency went down.

Lesson 2: Load Balancers have limits

The team experienced outages because Elastic Load Balancers (ELB) couldn't scale fast enough during new deployments. When DNS swapped to a fresh, unscaled ELB, it immediately hit out-of-memory (OOM) errors under the massive traffic.

Fix: They switched to Application Load Balancers (ALB), which stayed persistent across deployments. However, this revealed a quirk: ELBs use "least connections" routing, while ALBs use "round robin," which slightly increased their tail latency (p99).

Lesson 3: Not all cache libraries are equal

Initially, they used Google’s Guava cache. However, Guava performs cache maintenance during request cycles, which can "hiccup" response times.

Fix: They swapped Guava for Caffeine. Caffeine performs maintenance in the background and prevents "thundering herds" (multiple requests hitting the DB for the same expired key). The result was a dramatic smoothing of their latency graphs.

Yes, the language used is Java ☕️

Lesson 4: The Sidecar Pattern

Despite a rock-solid service, some internal client teams still saw high latency. The culprit was a poorly configured HTTP pools or sequential retry logic in the client code.

Fix: Atlassian built a client sidecar. This is a small container running on the same pod as the client application. The sidecar handles:

Long-lived local caching

Parallel requests by calling AWS regions simultaneously and returns the fastest response.

Simplified Integration where clients just call

localhost, and the sidecar handles the complex multi-region logic.

Result: 0.7ms Latency

By moving logic into a sidecar and optimizing every layer of the stack, Atlassian achieved p99 latencies of ~0.7ms from the client's perspective with near 100% reliability.

The biggest takeaway from this article would be cloud is not a magic. You still need to do a great deal of engineering.

TCS’s Journey to 6-9s of Availability

Atlassian also published another article on TCS where they showcase how the team improved the system to constantly achieve 99.9999% of availability. To put that in perspective, that is only 32s downtime every year.

This is an amazing feat.

How do they do it? By evolving their sidecar from a simple cache into a sophisticated, defensive intelligent agent that runs on over 10,000 nodes.

The "Fail-Slow" Defense: Region Isolation

One of the hardest things to handle in distributed systems isn't a "fail-fast" (where a service just dies) but a "fail-slow" (where a service becomes sluggish).

To solve this, the TCS sidecar doesn't just wait for a timeout. It preemptively sends duplicate requests: one to the primary region and one to a random secondary region.

This is often called hedging.

The first response to return is used; the other is discarded.

If a secondary region starts lagging, the sidecar automatically shrinks its thread pool and starts load-shedding. This prevents a slow region from clogging the sidecar’s CPU and memory.

Taming the Invalidation Storm

At Atlassian's current scale—serving 32 billion requests per day—a single write update could trigger millions of SQS messages due to the "fanout" effect to 10,000+ nodes.

To prevent melting AWS’s SQS infrastructure, they implemented batching:

Instead of sending messages instantly, they accumulate updates for 1 second.

This simple 500ms delay stabilized their burst traffic and significantly cut costs.

Solving the "Traffic Blackhole"

A node is healthy according to the load balancer, but it’s actually a zombie - the process is up, but the network or DNS is broken.

Under a Least Outstanding Requests (LOR) strategy, these zombie nodes respond with errors instantly, making them look fast. The load balancer then sends them even more traffic, creating a blackhole.

Atlassian integrated the sidecar into the node’s local health check. If the sidecar loses its connection to the parent TCS and its cache goes cold, it tells the load balancer: "I'm not healthy, take me out of rotation."

Advanced Optimizations

CacheKey Broadcasting: For services that scale very wide, the request rate per node is low, leading to cold caches. Sidecars now talk to each other, broadcasting which keys they have cached so neighbors can pre-warm their own memory.

Auto-Decryption: The sidecar now includes

AutoDecryptors. It handles the envelope decryption (via AWS KMS) before caching the data. This means the client application gets plain text instantly, with zero overhead.gRPC: By switching from REST to gRPC, they improved p90 latencies from spiky 2ms+ down to a stable 600-750 microseconds.

The "Poisoned Data" Lesson

Perhaps the most insightful part of the article is the empty table incident. A data migration caused a DynamoDB table to be empty. The system was "up," but it was returning valid 404 Not Found responses for everything. The sidecars faithfully cached these 404s, essentially taking the cloud offline.

Fix: The sidecars are now "suspicious."

Content Checks: They regularly fetch "dummy keys" that must exist. If they get a 404, the parent TCS is marked as "untrusted."

Consensus Monitoring: The sidecar compares the 200 vs. 404 ratio across all parent regions. If one region deviates from the "consensus," it’s dropped immediately.

That’s it for today. Both the posts are heavily technical on reliability and availability of systems. But they are fantastic reads for engineers who enjoy working on reliability of systems. Hope you liked the episode!

Until next time! ✌️

Reply